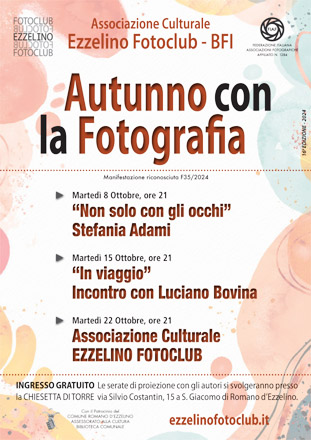

Una “delegazione” del nostro club (in realtà solo la nostra socia Chiara Didonè) ha potuto visitare l’antologica di Henry Cartier Bresson presso il Centre Pompidou a Parigi. L’impressione che ne è derivata è di un evento che giustificherebbe un viaggio apposito nella capitale francese, in quanto altissimo livello e con più di 500 pezzi tra documenti e fotografie originali stampate dall’autore.

Rising signs

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographic work began in

the Twenties. It arose from a combination of factors:

an artistic predisposition, unremitting study,

personal ambition, a little spirit of the times,

personal aspirations and a great many encounters.

He studied under André Lhote from 1926 to 1928,

learning the classic rules of geometry and

composition. He first applied these to his painting

before experimenting with them soon afterwards

with his camera. His first pictures are thus often

structured according to the proportions of the

Golden Section. Thanks to his American friends

Caresse and Harry Crosby, he discovered Eugène

Atget’s photographs of oldParis. Starting in the

autumn of 1930, he spent a period inAfricawhere he

applied the formal innovations of the New Vision in

photography, inherited from Russian Constructivism:

unusual angles, extremely close-up shots and

an attention to dynamics. A far cry from

the ethnographer’s point of view, these pictures

are marked by the rhythm of Africans’ daily lives.

The attraction to Surrealism

Through René Crevel, whom he met at the home

of Jacques-Émile Blanche, Cartier-Bresson began

to mingle with the Surrealists in around 1926.

The elements of chance and coincidence that

Cartier-Bresson included in his compositions,

like the movement captured in his shots, all evinced

his sympathy with this movement, although he was

never an official member of it. However, he regularly

attended the meetings of the group’s members.

From these associations, he retained a number

of motifs emblematic of the Surrealists’ world,

like wrapped objects, deformed bodies and dreamers

with closed eyes. But he was even more influenced

by the Surrealist attitude: the subversive spirit,

a liking for games, the importance given to the

subconscious, the joy of strolling through the streets,

and lightning speed.

A militant commitment

Like most of his Surrealist friends, Cartier-Bresson

shared many of the Communists’ political positions:

a fierce anti-colonialism, an unswerving commitment

to the Spanish Republicans and a profound belief

in the need “to change life”. His first photo-reports,

commissioned by the Communist press, dealt with

social subjects like the first paid holidays in 1936, or

paid tribute to Party ideals, like “childhood”. He also

covered political meetings. During the coronation

of George VI in May 1937, he mischievously turned

his back on the sovereign and pointed his camera

at the people looking at him.

Cinema and the war

Cartier-Bresson’s experience in films contributed

to his political commitment. Between 1935 and 1945,

he abandoned photography for film, whose narrative

structure made it possible to reach a wider audience.

In theUSin 1935, he learned the basics of using

a film camera from a cooperative of documentary

makers, led by Paul Strand, who were highly inspired

by Soviet political ideas and aesthetics. The name

of the group was “Nykino”, from the initials of

New Yorkand the Russian word for cinema. On his

return toParisin 1936, he began a collaboration with

Jean Renoir that lasted until the war. He enlisted

in the Film and photography sections of the French

Troisième Armée during the Second World War, and

spent three years as a prisoner before escaping and

joining a group of Communist resistance fighters.

Between 1944 and 1945, he filmed and photographed

documentary images of the ruins of the village of

Oradour-sur-Glane, the liberation ofParisand

the return of prisoners fromGermany.

The decision to become a photojournalist

The retrospective devoted to Cartier-Bresson by

the MoMA inNew Yorkin February 1947 marked

the institutional recognition of his creative genius.

The same year, he cofounded the cooperative

Magnum Photos, and focused on photojournalism.

From then on, he accepted the constraints of the job,

in terms of technical requirements and the topicality

of the subjects. His pictures were published in

magazines all over the world until the early

Seventies. Some made a particular impression

on the public, like the crowd of Indians in mourning

during Gandhi’s funeral, or the “gold rush” of

the Chinese. On the sidelines of these events, he also

showed people’s daily lives in different countries:

inRussiaafter Stalin’s death, inCubain 1963, and

inFranceafter the disturbances of May 1968.

Visual anthropology

In every country he visited for his reports,

Henri Cartier-Bresson observed and photographed

recurring themes and shared attitudes resulting

from the upheavals in society after 1945. Like an

anthropologist, in direct contrast to the pace and

constraints imposed by the press, he carried out

a number of surveys focused on certain themes

across the board throughout the world.

These reflected his pre-war interests and

obsessions: choreography and the depiction

of bodies in cities, the relationship between men

and machines, the representation of power in public

space, signs of the consumer society and those

involved, and crowds – the embodiment of

the revolutionary spirit, and also a highly stimulating

exercise in photographic composition.

After photography

From the Seventies onwards, Cartier-Bresson began

to distance himself from Magnum and gradually

stopped taking commissions for photo-reports.

While he did not abandon his Leica, his style became

more collected and contemplative. The landscapes,

portraits of friends and objects in his personal life

that he captured on film evoke the poetic spirit of

his early pictures. In a similar return to his roots,

he went back to drawing, sketching in the open air or

from life. He spent a great deal of time supervising

the organisation of his archives, sales of his prints

and the production of books and exhibitions.

Slowness and observation imbue this final period

in the work of an artist whose keen eye produced

magnificent results, in every facet of his career

and in every medium he used.

Henri Cartier-Bresson

1908 Henri Cartier-Bresson is born on 22 August

in Chanteloup-en-Brie.

1926-1928 René Crevel introduces him

to the Surrealists. He attends several meetings of the group,

whose members have joined the Communist party.

He studies at the academy of painter André Lhote.

1929 He becomes friends with the American couple

Harry and Caresse Crosby. At their home, Cartier-Bresson

meets up with André Breton and Salvador Dalí again.

He gets to know publishers, gallery owners and collectors,

including Julien Levy. He learns about the formal innovations

of American Straight Photography and the European

New Vision.

1930-1932 Cartier-Bresson sets off forAfrica.

On his return, he goes on a journey toEastern Europe,

then travels toItalywith his first Leica.

1933 He begins to mingle with the AEAR (association

of revolutionary writers and artists) inParis. He visits

a number of cities inSpain, and carries out his first

photo-reports for the press.

1934 After the February riots inParis, he signs two

anti-Fascist tracts. In June, he begins a year-long stay

inMexico, mixing with artists and intellectuals who have

close ties with the National Revolutionary Party then

in power.

1935 He goes toNew York to take part in the exhibition

“Documentary and Anti-Graphic Photographs by

Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans & Álvarez Bravo”

at Julien Levy’s gallery. He becomes involved with Nykino,

a cooperative of militant pro-Soviet film directors.

In May and June, he participates in the exhibition

“Documents de la vie sociale” staged by the AEAR inParis.

He gradually focuses on films more than photography.

1936-1939 Cartier-Bresson meets Jean Renoir.

He becomes his assistant on La vie est à nous, commissioned

by the Communist Party. He collaborates on Partie

de campagne and La Règle du jeu, and works regularly

for the Communist press. In 1937, he marries the Indonesian

dancer Carolina Jeanne de Souza-Ijke, known as Eli

(they divorce in 1967). A member of the Ciné-Liberté

cooperative (the film section of the AEAR), Cartier-Bresson

produces his first documentary, Victoire de la vie,

on the Spanish Civil War.

1940-1945 He enlists in the “Film and photography”

section of the Troisième Armée. He is taken prisoner,

but escapes in 1943, and withAragon’s help joins a group

of Communist resistance fighters, the future MNPGD

(National Movement for Prisoners of War and Deportees).

He becomes its official representative in the Comité

de Libération du Cinéma and is put in charge of organising

a Comité de Libération dela Photographiede Presse.

In 1945, the Office of War Information and the MNPGD

assign him to direct a film on the repatriation of prisoners

(Le Retour).

1947 First retrospective at the MoMA. He founds

the Magnum Photos cooperative with Robert Capa,

George Rodger, David Seymour and William Vandivert.

His photo-reports appear in numerous magazines like Life,

Holiday, Illustrated and Paris Match. In December,

he travels toIndiawith Eli, shortly after the Declaration

ofIndependence.

1948 He meets Gandhi, just before his assassination.

His photographs of the funeral are published by Life.

Then he travels toBeijingjust when the People’s Liberation

Army led by Mao Zedong is on the brink of toppling

Chang Kai-shek’s Nationalist government.

1952 He publishes his first book with the art critic

and publisher Tériade: Images à la sauvette or

The Decisive Moment in the American version.

1954-1955 Danses àBali is published with

a foreword by Antonin Artaud. Cartier-Bresson travels

toMoscow, as the first Western reporter to enter

the URSS since 1947.

In 1955, he takes part in the exhibition “The Family of Man”

at the MoMA. The Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Paris

devotes a retrospective to him. He publishes Les Européens

with Tériade.

1963-1965 He travels toCuba, then spends several

months inJapan.

1966 He meets the photographer Martine Franck,

whom he marries in 1970.

1968-1974 After May 1968, he begins a report

on his compatriots: Vive la France. From 1974 onwards,

he gradually abandons photojournalism in favour of portrait

and landscape photography, and the promotion of his work.

He takes up drawing again.

1979 The book Henri Cartier-Bresson: photographe is

published to accompany the eponymous travelling exhibition.

1980 The Musée d’Art Moderne dela Ville de Paris

presents the exhibition “Henri Cartier-Bresson:

300 photographies de 1927 à 1980″.

2003 The Bibliothèque Nationale de France presents

the retrospective “De qui s’agit-il?”

The Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson is created inParis.

2004 Henri Cartier-Bresson dies on 3 August

in Montjustin.